Glass Walls and Finance Capital

Jocelyn Olcott

18 February 2024Alicia Girón’s open-access book Economía de la vida offers a comparative perspective on the ways that financialized capitalism has shaped the care economy.

This post forms part of what we anticipate (to the extent that we’re confident anticipating anything these days) will be a short series on publications that didn’t receive as much attention as they might have because they appeared during the Covid lockdown, when many people were, well, bogged down in carework.

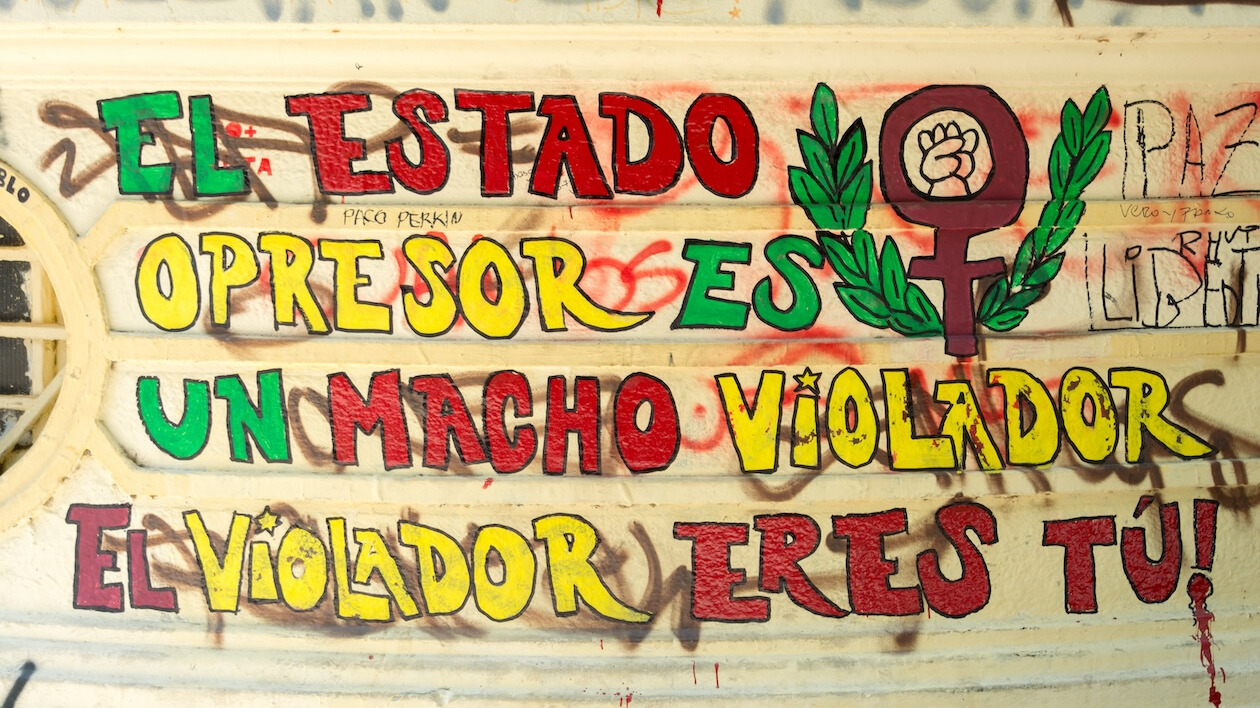

Alicia Giron’s open-access e-book, Economía de la vida: Feminismo, reproducción social y financiarización (CLACSO, 2021), begins and ends by pointing out that the Chilean feminist protest group Las Tesis, in their now-famous anthem “El violador eres tú” (“The rapist is you”), point their collective finger at the state. “It’s not just a metaphor when the group Las Tesis names the State as a rapist,” Girón explains. “Violence against women, economic as well as physical, is connected to the absence of public policies with a focus on gender” (235) In the chapters that comprise this volume, Girón gives us the public policy context for the relentless gender violence examined by writers such as Sayak Valencia and Kate Manne.

Apart from the introduction and conclusion, the chapters collected here were all written before the pandemic and lightly updated for this volume. Thus, the principal conjunctural moment in most of these essays isn’t Covid-19 but rather the 2008 global financial crisis. This orientation allows Girón to demonstrate that most of the problems that were set in relief by the pandemic had their roots in the policies of the preceding decades.

In accessible, non-jargony language, the essays collected here bridge the divide between Anglophone and Hispanophone scholarship and between interventions in critical feminist theory and UN development reports. Although these chapters mostly center on policy effects in Mexico and Latin America, Girón considers data from around the world to make a case for the impact of various policies in mitigating problems such as wage inequities and the distribution of household labor. Some issues, such as the effects of migration and the remittance economy, are helpfully analyzed here from the perspective of migrants themselves.

Girón is particularly attentive to the promises emerging from the UN Decade for Women (1975-85) and the various iterations of UN development goals, specifically the objective of “gender equality and women’s empowerment.” By way of immanent critique, she holds up the UN’s — and therefore UN member states’ — stated aims to offer persistent reminders of states’ own commitments to promoting gender equality.

Importantly for readers of Care Talk, Girón consistently returns to the ways that the maldistribution and undervaluation of care work reflect neither microeconomic price curves nor macroeconomic metrics such as GDP but rather the mesoeconomic structures, institutions, and processes that mediate economic relationships. Citing Susan Himmelweit, Girón argues for greater attention to practices such as gender budgeting and attending to the gender implications of macroeconomic policies. She also points to the ways that women encounter not only glass ceilings but also glass walls, or what Nancy Folbre has described as a care penalty, in which the paid care sector is systematically undervalued (207).

One example that Girón turns to several times throughout the book is that of microcredit. The idea of providing small, easily secured loans to women emerged from a feminist project in the 1970s to address the fact that women often lacked the assets that could serve as collateral for even small loans to start their own businesses. In an era when coverture laws (including in the United States) continued to prevent married women from having access to credit, providing women with an avenue for financial autonomy within their households was a core feminist objective.

By the time Girón was writing these essays, however, the liberatory possibilities of women’s microcredit had given way to the usurious habits of finance capitalism. As Alba Carosio explains in her prologue, microcredit created a “false discourse of emancipation and empowerment, with the illusion that poor women would become ‘entrepreneurs.’ … This basis does not provide the necessary infrastructure for the services required by the communities. Microcredits do not promote energy or water systems or health and education services” (14-15).

As Girón details, “Women are the candidates for microcredits because it is the easiest way to include them in the labor market circuits, as well as in the financial circuits, due to their high degree of commitment to their families and their work” (105). Microcredit programs pulled women into the banking system, trained them to develop business plans based on maximizing efficiency and return on investment, and promised a form of “development from below” that shed the paternalist impulses of mid-century development schemes. Drawing on MIX Market data provided by the World Bank, however, Girón assembles extensive evidence about the ways that microfinance, when it is taken up by the rent-seeking financial sector, commands extraordinarily high interest rates. In Mexico between 2005-6, for example, rates vacillated between 23% and 103% on average (123).

This sustained attention to financial questions — including not only microcredit but also monetary and fiscal policies — explains the context in which women in many parts of the world find themselves find themselves performing a “triple shift” of work in the formal and informal economies as well as the care labors performed for their households and communities (23). None of the UN’s well-intentioned development goals, Girón reminds us, can be obtained without attention to the public policies that structure landscape of possibilities.

Other chapters focus on the policies that Girón sees as particularly critical for closing what the World Economic Forum has dubbed the Global Gender Gap. These mostly center on a familiar constellation of measures that would allow women to take better advantage of educational and employment opportunities by relieving them of the triple shift — affordable, available, high-quality childcare; generous paid maternity and paternity leaves; workplace lactation facilities, etc. Such policies, Girón emphasizes, require strengthening welfare states, restoring central banks as lenders of last resort, and extricating the care economy from financialized capitalism.

Girón keeps her focus squarely on gender and the data specific to sex differences. To the extent that she gestures to other forms of inequality, it is primarily to indicate that they follow the same patterns. When she distinguishes among women at varying degrees of economic risk (226), it is to reveal the geographic differences among the pandemic’s impacts.

Girón returns us to the viral spread of the Las Tesis protests to remind readers that a new wave of feminist activism has emerged to challenge the imbricated threats of gender violence and the devaluation of social reproduction. The green and purple tides that have washed over Latin America, demanding reproductive justice and an end to gender violence, include massive strikes and demonstrations every March 8 to highlight the value of women’s paid and unpaid labor.

Image credit: Carlos Figueroa Rojas

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.