Resisting Gilead

Jocelyn Olcott

9 March 2024The New-York Historical Society hosts an all-star lineup to discuss histories and possible futures of care.

In honor of Women’s History Month and in conjunction with an exhibit on the history of women’s work, the New-York Historical Society hosted a series of conversations among an impressive lineup of scholars, activists, and journalists discussing various aspects of care and carework.

Although it wasn’t explicitly part of the event’s framing, the implicit periodization centered on the impact of neoliberalism in the last decades of the twentieth century, compounded by the 2008 financial crisis and the 2020 pandemic. Historian and conference organizer Anna Danziger Halperin pointed to sociologist Jessica Calarco’s observation during the Covid-19 pandemic that, “Other countries have social safety nets. The U.S. has women.”

The reporter Sara Luterman opened the first panel with the question of how we define care and who performs it. Sociologist Rhacel Salazar Parreñas pointed to definitions such as Nancy Folbre’s and Paula England’s that carework involves principally face-to-face services as well as Mignon Duffy’s distinction between nurturant and non-nurturant forms of care labor. Historian Sherie Randolph drew on research from her forthcoming book about “bad Black mothers” who reject the expectation that Black women will step into the role of mothering all those around them. And Emma Amador drew on research from her forthcoming book, based on interviews with Puerto Rican women — including her grandmother — who arrived in New York City as domestic workers in the 1940s and organized for social and labor rights.

Parreñas pointed to that, around the world (except Italy!), there are migrant careworkers who labor under a form of indenture — a practice we usually think of as ending sometime in the nineteenth century, giving way to less coercive practices. Migrants to Israel can switch employers within the first 63 months but not thereafter. In Singapore, workers must seek permission from their employers, who can either “release” workers to find a new sponsor or “cancel” them, requiring them to leave the country. In the United States, as Grazi Valentim pointed out in an earlier post, au pairs are required to find a new sponsor within two weeks of termination.

The second panel, moderated by the eminent labor historian Alice Kessler Harris, explored the ways that the combination of rolling back of social-welfare provisions and women’s increased participation in paid labor left families turning to market solutions for care needs. Kessler Harris pressed the panelists on whether the term “carework” isn’t an oxymoron — whether performing carework for a wage fundamentally changes its nature. The panelists George Aumoithe, Anna Danziger Halperin, Premilla Nadasen, and Lara Vapnek generally challenged this dichotomy, pointing to the ways that paid careworkers demonstrate emotional investments in their jobs even as they resist exploitative labor conditions.

Discussion turned to the ways that private equity investments in the care sector have drawn public notice — Kessler Harris pointed to a recent article in The Atlantic about childcare, and The New York Times ran a similar assessment last summer regarding hospice care. The for-profit care sector has a poor record for both labor conditions and quality control, but it has become pervasive. As the economist Daniela Gabor has argued, private-equity investment has been drawn by the transformation of infrastructure — including care infrastructure — into an asset class for which governments mitigate all or most of the risk.

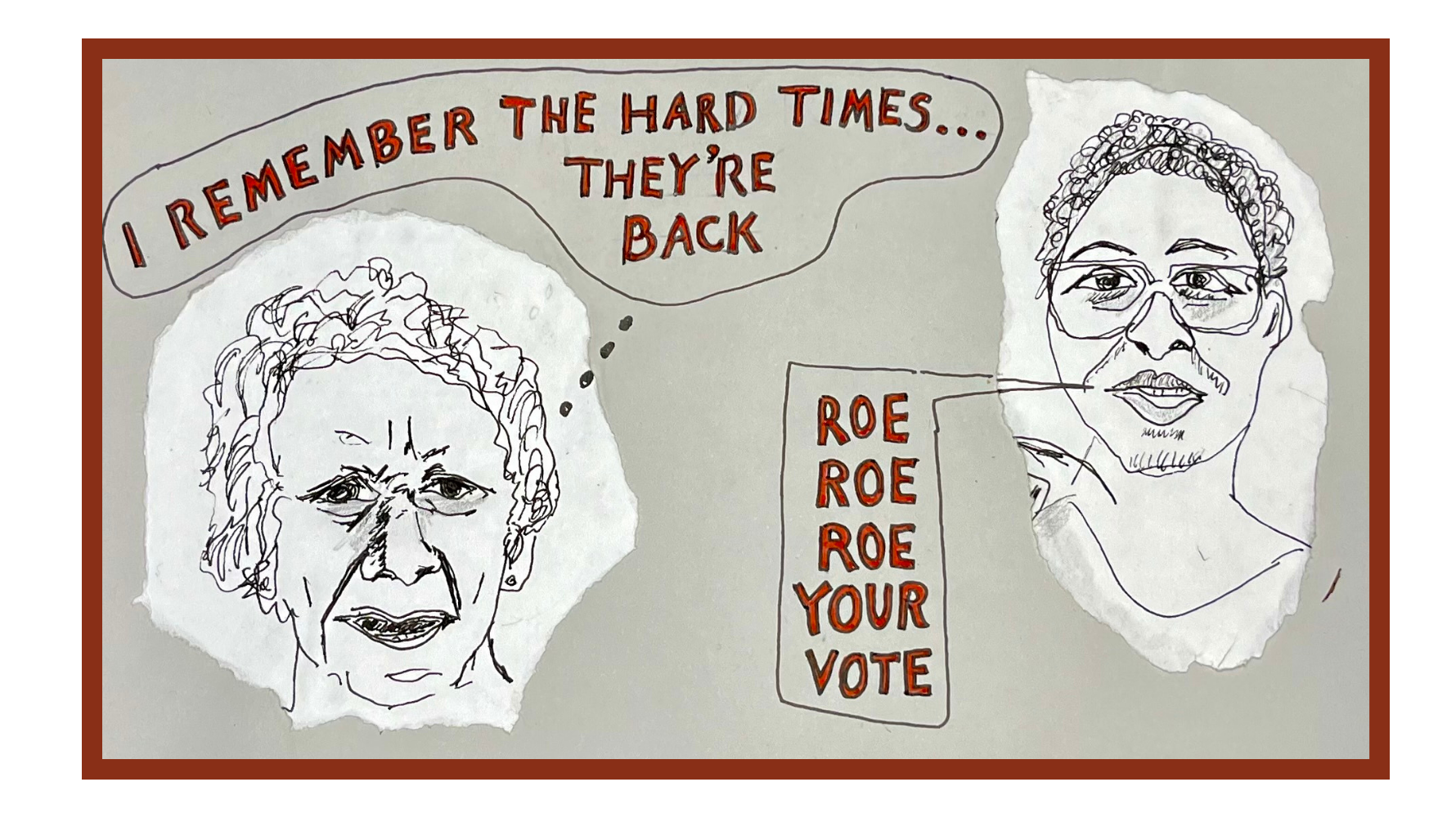

The third panel turned to a variety of efforts to build more care-centered societies from the ground up, often through, as moderator Salonee Bhaman described it, networking and radical information sharing. Laura Kaplan of the Jane Collective described how its members learned to perform abortions during the pre-Roe years in order to provide low- and no-cost abortions to women who needed them. Margaret Lowenstein explained how the AIDS epidemic fostered the ethos and practice of harm reduction that is now a central tenet of addiction treatment. Harm reduction itself, she explained, entails mutual aid and information-sharing within the harm-reduction community. Laura Mauldin’s website Disability at Home provides a photo essay and explanations about how people with disabilities and their caregivers have come up with ingenious ways to make their own homes more accessible. The Reverend Canon Eva Suarez explained that the half-century since women have been allowed to be ordained as priests in the Episcopal Church was concomitant with the elimination of social welfare programs, meaning that the growing number of women clergy has coincided with the clergy’s increased responsibility for care, particularly in intimate settings of extreme duress. The panel members discussed ways to create spaces of care and to bring care into the spaces where people need it most.

In the final session, New York magazine reporter Irin Carmon led a conversation with legal scholar (and Strict Scrutiny co-host) Melissa Murray and historian Deirdre Cooper Owens about the implications of the Alabama Supreme Court’s decision granting fetal personhood to frozen embryos. If the third panel offered optimistic narratives of all the ways that people have organized to obtain care, including reproductive care, this final session offered some timely but — I’m not going to lie — pretty depressing reminders of where we are now. Murray particularly stressed that footnote 41 of the Dobbs decision makes a case for fetal personhood as matter of anti-discrimination law. Despite Justice Bret Kavanaugh’s reassurances in the Dobbs hearing that women would always be able to travel for abortion care, the Alabama attorney general has claimed the right to prosecute those who facilitate out-of-state travel to seek an abortion. We are, as Murray put it, slouching toward Gilead.

The cover picture is designed by Nancy Folbre

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.