The Home, School, and Street: Exploring the Everyday Geographies of Caregiving Youth

Elizabeth Olson and Leiha Edmonds

10 March 2024Drawing on findings from a multi-year, mixed-method research project in collaboration with caregiving youth, young people under the age of 18 who take on caregiving responsibilities to support a parent, guardian, relative, or sibling who is chronically ill, disabled, or otherwise requiring care for medical reasons, we offer a critical examination of the ways young people’s everyday geographies of care in the home, the school, and the street, illustrate the importance of understanding ableism not only as oppression of the nonnormative body-mind, but also as the repression of the ability to give and receive care.

Zavia is twelve years old. He loves basketball and skateboarding. He works hard in school even though it is one of his greatest sources of stress. His apartment development does not have many other children, and like other low-income neighborhoods of Palm Beach County, Florida, it is situated closest to partially abandoned strip malls and small industries rather than other housing developments. Zavia also has substantial responsibilities providing care for his mom, who has a degenerative disorder that requires support with mobility, pain management, and medication. She had to cut down on her work after her illness accelerated and made walking and sitting difficult or impossible. Her multiple surgeries yielded little success in improving her well-being. She is isolated from her extended family, and as a single mom with very limited nursing support provided through federal programs, Zavia helps her get up in the morning, does chores around their apartment, and at night, he goes along with her on DoorDash delivery rides before helping her when it is time to go to bed. His mom pieces together bits of work that her former employer can allow her to do from home, but it is difficult to have consistency with medical appointments, surgeries, and weeks of debilitation.

Zavia has little time or resources to pursue other hobbies or interests, but he enjoys time with a mentor and one of the friends that he can see when he has some free time, and when his mom feels confident letting him go to the basketball court. She worries about his safety as a Black-Puerto Rican boy; he worries about what would happen if his mother gets any sicker. When we asked him what he wishes adults would know about his life and his responsibilities, he explained, “…not every kid has a perfect parent with no problems. Most kids have parents to help…when there are issues that you need to take care of, and some unlucky kids don’t have parents at all… and you never know what the outcome of your life [is], especially as a kid.”

In the intricate tapestry of contemporary neoliberal capitalism in the United States, the experiences of young caregivers like Zavia serve as a poignant lens to explore the pervasive nature of ableism. Our ongoing collaboration since 2021 with fifty caregiving youth aged 11 to 18 in Palm Beach County, Florida, suggests the nuanced and complex ways in which caregiving intersects with the identities of these young individuals, shaping the spaces and places available to them and illuminates how ableism is ingrained where caregiving occurs.

In the U.S., it is estimated that approximately 5.4 million children and adolescents provide care for someone in their family or household who requires support due to chronic illness, disability, or other conditions associated with medical diagnosis (AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving, 2020). Caregiving youth (also “young carers” in much of the world) often provide care before or after school and through weekends. They might support other families with care activities or be the sole informal care provider. The types of activities that they undertake vary greatly, not only according to the kinds of care required in their family or household, but also due to intersections with race, class, citizenship status, gender, and other aspects of both embodiment and identity.

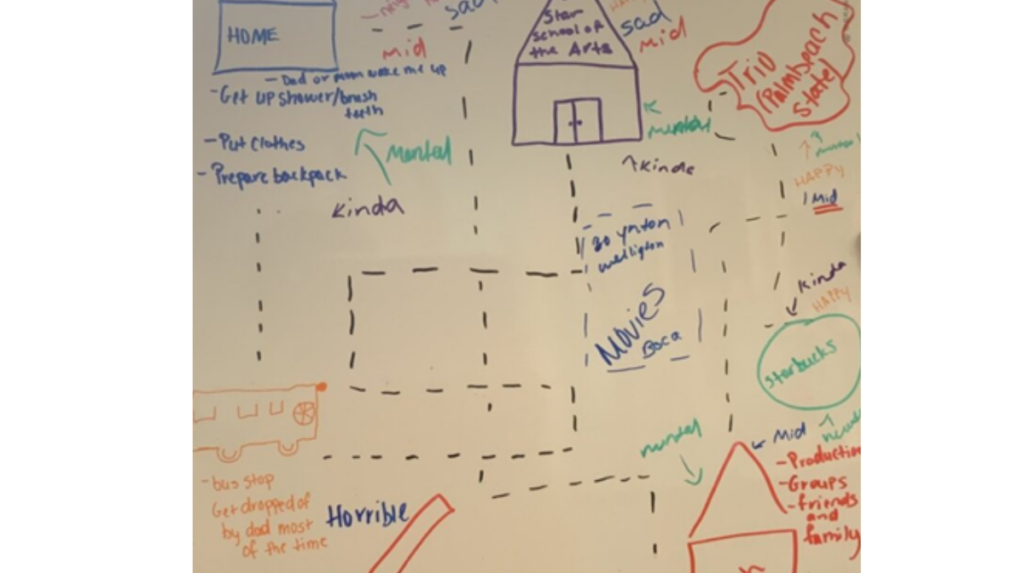

Our research with caregiving youth brings together geospatial and sketch mapping data on young people’s experience of place and emotion, audio and written diaries, and oral histories of care. A central theme emerging from our study is the profound impact of care relationships on the constitution of places. The characteristics of places, whether homes, schools, or streets, are fundamentally altered by the presence of caregiving youth. At the same time, our research examines how spaces are shaped by and for ableism. Transcending the narrow focus on the disabled body, our research shows how caregiving youth navigate intricate webs of relationships and practices that sustain life and well-being in the face of ableism. We suggest that critical understandings of ableism can be enriched by delving into the everyday experiences of caregivers.

By incorporating care explicitly into analyses of ableism, we align with disability justice and crip-queer activists who caution against assuming that all care is inherently beneficial. Recognizing the ambivalence of care, with its contradictions and complexities, aligns with existing scholarship on care ethics in geography.

The ableism ingrained in contemporary society manifests itself in the spaces where caregiving unfolds. The home, often a sanctuary for families, becomes where the financial precarity of being a disabled head of household can lead to chronic housing insecurity. School environments, often unaware of or indifferent to the caregiving duties of students, contribute to stress and perpetuate narrow definitions of acceptable care. The street, an ostensibly neutral space, exposes caregiving youth to challenges such as the need to transition from hands-on care to seeking employment outside the home and concerns about the hostility of speeding cars and limited crosswalks that a family must navigate.

The narratives of young caregivers highlight how ableism permeates their daily lives, influencing their ability to provide care and shaping the environments in which they operate. In the pursuit of justice, our research participants also articulate a vision of desired worlds. Their aspirations encompass wishes for care to be easier, for prejudice against nonnormative body-minds to end, and for adults to take them seriously as family caregivers. These young individuals embody creative solutions and mutual support, challenging the constraints imposed by neoliberalism. However, their realism about their roles and contributions tempers any romanticization of their experiences. As we delve into their experiences, we uncover a rich tapestry of challenges, resilience, and the need for systemic change. By acknowledging and addressing the ableism ingrained in the places and spaces where caregiving occurs, we show the importance of understanding ableism not only as oppression of the nonnormative body-mind, but also as the repression of the ability to give and receive care.

Cover image by DisobeyArt. Internal Image in the article, own image by the authors.

Author’s image and text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.